Each of the 11 galleries at the National Museum of Qatar presents different material histories of the country, across time and geography. In the Life on the Coast gallery, we learn about the UNESCO World Heritage Site Al Zubarah, once a thriving pearl fishing town and trading port, whose remains entomb a powerful past.

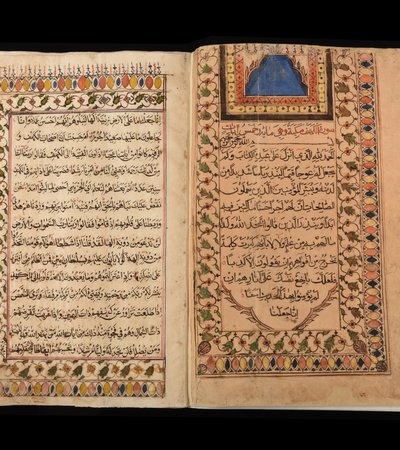

Qatar's history is often reduced to an oversimplified narrative: an economic structure sustained entirely by pearl diving until the discovery of oil and gas in the twentieth century; a capital in the desert that came from nothing. The full story of Al Zubarah shows us what these narratives leave out: a historically complex and resilient urban Islamic society that, as a centre of pearl trade and a tax haven, attracted the attention of neighbouring empires. It survived multiple, competing threats for over a century and is an important example of indigenous political, cultural and economic independence that flourished in the 18th and 19th centuries.

While some aspects of Al Zubarah’s history remain unclear, archaeologists have determined that there were six different phases of development across the site. Its first known origins can be dated to the 1760s, when tribal groups from around Al Basrah and Kuwait took on the collective name of Utub. Settling on a rocky stretch of land by the sea, they escaped the expanding imperial ambitions of Persia and ensured the continuation of their social and economic independence. Although this settlement lacked the most precious resource – fresh water – it soon prospered and became an important trading port, a conduit for the exchange of commodities and ideas from across the region.

After the initial settlement, Al Zubarah was massively expanded through the construction of an outer town wall, large fortified buildings, courtyard houses, a souq, mosques and the development of an urban street grid. This phase is believed to have lasted for a period of 50 years, until the early nineteenth century.

Al Zubarah’s position as a vibrant trading port left it vulnerable to attack, and historical sources and archaeological excavations reveal evidence of the town being attacked multiple times. It receded into fortified safety, remaining resilient against threats posed by the expansionist ambitions of the Ottoman, European and Persian empires.

Historians associate a widespread fire across the site with an attack by forces from Muscat in 1811, leading to a phase of repair and the emergence of temporary structures. Around the 1820s, stone houses began to replace the temporary structures, but the settlement with a small pearling community only redeveloped to about a third of its original size.

By the early twentieth century, the site was no longer urban, with archaeological evidence suggesting that it was used primarily as a place for seasonal encampment by nomadic people.

Finally, archaeologists note that although there was some construction done on the site after the 1950s – a pier and a road – the settlement was largely empty. There is ambiguity around how the story of Al Zubarah ended, and research is ongoing to establish clear chronological correlations between archaeological discoveries and written sources and oral histories.

What we know for sure is that excavations of the site have revealed extraordinarily high levels of social planning, and organisation of natural and human resources. The street grid and general layout of the neighbourhoods suggests the presence of a centralised planning system. The town once stretched 1,500m from north to south and up to 650m from east to west, and historians ascertain that it had a permanent population of 5,000 to 6,000 people with up to 9,000 at its height, and an additional seasonal population of many more during the summer pearling periods.

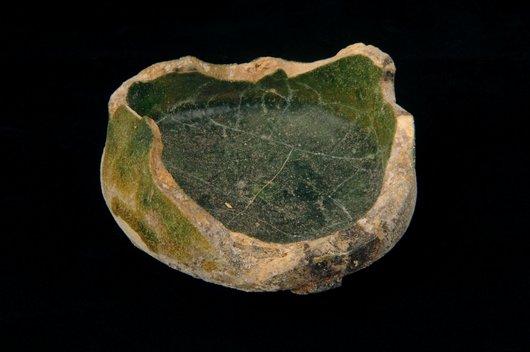

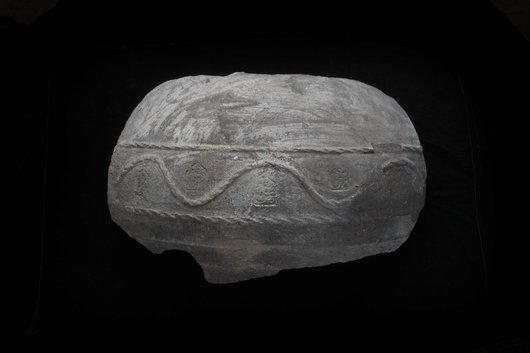

Historians consider Al Zubarah a crucial stepping stone towards Arab independence in the Gulf, and its story – filled with prosperity, resilience and intrigue – is one you can encounter today in the galleries of the National Museum of Qatar. The Life on the Coast gallery presents a large-scale model of the archaeological site, against the backdrop of an art film directed by Abderahmane Sissako, which captures the rhythm of day-to-day life in the trading port. Artefacts on display – from everyday wares such as jars and dishes and oil lamps, to remnants of window décor, to diving weights made from a heavy, dark stone – open a window into the once bustling town.