Q. Could you talk us through the conceptualization of this exhibition, the curatorial decisions that went into choosing these three specific groups and the vocabulary used to categorise them?

Dr. Lila Abu-Lughod: Conceptualising this exhibit was complicated, collective and absolutely fascinating. For someone like me, who is more used to writing, it was an intensely intellectual challenge. How can you communicate knowledge and fresh ways to think about the world to wider publics without sacrificing depth or nuance?

We actually began not with a concept but with some remarkable objects in the collection of the National Museum. Dr Alexandra Bounia, an experienced museum studies specialist, guided the team. I was “interpretive advisor.” I had lived with and written about former pastoralists, a Bedouin community in Egypt, and had read all the research that went into the making of the permanent galleries on Qatar’s pastoralist heritage.

We recruited specialist curators with impressive expertise on and experiences with pastoralists in the regions we had decided to focus on. We looked for anthropologists who understood the everyday worlds, material culture, languages, historical circumstances and scholarly debates about these communities, but had also spent years living with them. They, along with the Qatari experts from the museum who had worked on the permanent galleries, made up the group that developed the themes and structure of the exhibit. It was a process of intense give and take, discussion and experimentation. We shared a commitment to creating an innovative but carefully researched exhibit that would tell a story and make an argument that was relevant to anyone who cared about the future of our shared planet.

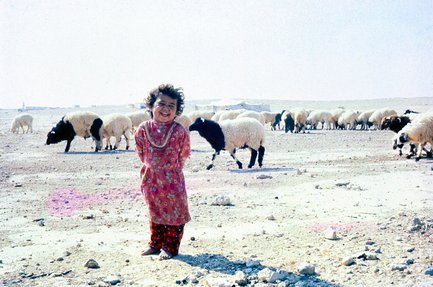

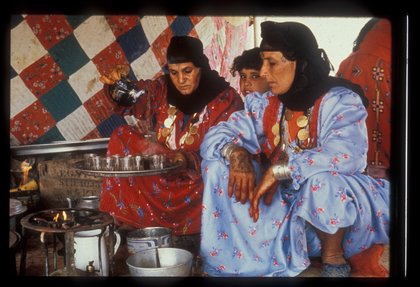

As curators and anthropologists, we wanted to share what we each valued about these communities we knew and admired—people who live with, care for and breed livestock. We wanted others to begin to think about what it means to live in moveable homes that don’t use up resources or leave permanent traces and to value the environments that nourish us. Could this way of living offer us all clues for how to live well with less damage to our fragile worlds?

It took more than a year of talking and planning, preparing research packets, arguing over terminology and considering what objects we had and could borrow to tell the story that unfolded gradually through our conversations.

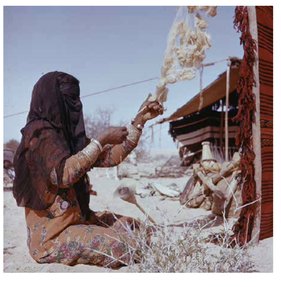

Qatar was at the centre, but we extended east to Mongolia, where the marvellous gers have inspired the yurts so popular in Europe for eco-glamping and even well-known American architects like Buckminster Fuller. We moved west to the Central Sahara to include the nomadic pastoralists with camels and goat herds who call themselves Imuhar (but are known to outsiders as Tuareg, again an important consideration we had about what terms to use).

The National Museum has an excellent collection of objects from Qatar as well as from Central Sahara. The conservators restored a large tent made of goatskins, exquisite carved wooden poles and milk bowls, windscreens woven by women, fringed leather bags and more. It turned out that Mongolia was a wonderful place to choose because the anthropologist who curated this material made close connections with colleagues at the Mongolian National Museum. They were excited to be a part of our exhibit. They generously shared what they had, including a full felt ger (yurt), jewellery, clothing, horse saddles, musical instruments and more. The National Art Museum also lent us some of their true national treasures of Mongolian art, depicting novel views of herders and their environments.

We didn’t want this exhibit to be just ethnographic, representing the groups and their ways of life in a stilted way, as “cultures.” These were three very different communities from different parts of the world, with distinct histories (colonial and otherwise), distinct political aspirations, and facing different challenges. To begin with, we imagined them as pastoralists—they all herd and live with animals. That’s what they have in common. They have moveable dwellings so they can pack up and move with herds. But their situations couldn’t have been more different. Some Imuhar are highly nomadic, packing a household’s possessions onto two camels to move. In Mongolia, where herders are a minority and herding families often split between town and country, we had the opposite situation. Contemporary herding was shaped by the history of Soviet colonialism and collectivization but now herders were in a neoliberal freefall in their country, with not enough support for this way of life. In Qatar, with the discovery of oil and gas, the semi-nomadic herding way of life was replaced with many other possibilities and opportunities. If pastoralists are those who live intimately with animals—goats, sheep, camels, horses, and more—yes, the three groups shared that. But we had to come to terms with what they didn’t share. This was a key lesson: we could not see any group as outside of history and politics.